The 106 minutes felt like months. Every moment pulsed with adrenaline

and fear, waiting for another German assault — bullets from behind,

bombs from above, torpedoes from below.

Some 400,000 soldiers utterly exposed — not storming the beach, but

retreating in the sand, only to be pummeled with a hailstorm of heavy

explosions. Only twenty miles of water stood between them and their

homeland (twenty-five world-class swimmers have been able to swim it).

But the Nazis made the English Channel an ocean for one week in 1940.

On the brink of military disaster in the Battle of France, Churchill

called for an immediate evacuation. He had hoped to rescue 45,000 men, a

horrifyingly small ten percent of the troops trapped at Dunkirk. He

believed the other 355,000 to be lost, save a miracle.

As many have written, Christopher Nolan has made a masterpiece, but I will not try to review

Dunkirk.

Dunkirk is the kind of movie that reviews you.

Strangers to War

The vast majority of my generation has never seen war like this.

Modern warfare, since the attack on 9/11, is real warfare, with real

risk and real causalities — devastating thousands of families. Brave

sons and daughters have been lost in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and

elsewhere. But the wars have not been felt across America like World War

I, World War II, or Vietnam. Many millenials, myself included, are

simply strangers to war.

I was not in danger while I watched

Dunkirk (except, maybe,

for a heart attack). But I felt the danger involved in that kind of war

more acutely than ever before. Everything is at stake. The next moment

is not guaranteed, or even expected. The enemy hides behind the corner,

under the water, and in the clouds. Death hangs over you at all times,

making every second of life so much more real, so much more urgent, so

much more precious.

A film like this holds a hundred lessons, but the next day, I feel one more deeply than the rest:

all of life is war.

The peace, comfort, and luxury of life in America today are lying to

us, lulling us into a spiritual nap, while hell hangs in the balance and

heaven makes hell against evil. The realities of World War II are far

closer to our actual reality. It may not feel like it, but we are

engaged in the greatest war ever fought. In fact, as followers of

Christ, it is not hard to see ourselves among the 400,000 at Dunkirk —

so close to home, yet surrounded on every side, and praying for

deliverance.

What Is War?

For strangers of war, life often feels more like

Call of Duty

than the Battle of Dunkirk. When we read passages about warfare in the

Bible, we’re more likely to picture ourselves on a couch with a

Bluetooth controller, than in an RAF fighter plane battling the

Luftwaffe.

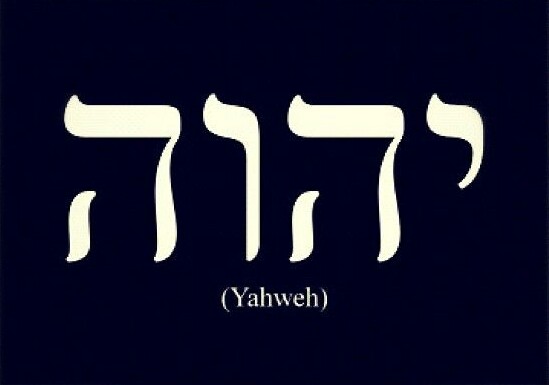

God says, “Beloved, I urge you as sojourners and exiles to abstain from the passions of the flesh, which

wage war against your soul” (

1 Peter 2:11).

Satan loves to shoot holes in the engine of our imaginations, and watch

fuel pour out of the meaning of the Bible’s metaphors. He wants us to

see “war” and think

video game, not

life and death. When the apostle Paul says, “Fight the good fight of the faith” (

1 Timothy 6:12), he meant

fight, not

play. He meant violent confrontation, not occasional recreation.

“We do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers,

against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present

darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (

Ephesians 6:12).

The worst wars in history are merely a shadow of the most important war

— the war that decides whether you spend eternity paying reparations

for your sins or celebrating your miraculous evacuation from

condemnation.

A movie like

Dunkirk makes

Call of Duty suddenly look like Candy Crush. And finally makes life feel like life, again.

War Within

The Bible uses war imagery to describe our battle against Satan and

all his demons, but it also uses war to describe what is happening

inside of us. The beach at Dunkirk is the shore of our hearts. The boats

are floating perilously on the waters of our thoughts and desires.

Temptations do not just hover over our heads, like bombs waiting to be

dropped at precisely the right moment, but they are planted like mines

in our indwelling sin.

James writes, “What causes quarrels and what causes fights among you? Is it not this, that

your passions are at war within you?” (

James 4:1). Similarly, Paul confesses, “I see in my members another law

waging war against the law of my mind and making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members” (

Romans 7:18–19,

23).

Are you aware of the battle being fought for your heart — the rifles,

tanks, missiles, bombs all being fired inside of you every minute of

every day? Are you prepared to fight for your life?

Sadly, we feel the weight of Nolan’s war far more acutely than we feel the weight of our own.

Mirage of Peacetime

Not everyone should see

Dunkirk. Even without graphic

violence or profanity, the relentless suspense may overwhelm many. But

we all need to feel the reality of war.

John Piper has said, “Until you know that life is war, you cannot know what prayer is for.”

The church never settles into peacetime, waiting for another Hitler,

or another Stalin, or another Kim Jong Un to rise. They are plastic

pawns compared with our enemy, and he never rests or surrenders. But his

defeat is secured, and his days are numbered. The English Channel

between us and victory is a lifetime of fighting a war we cannot lose.

Every new day is a new battle, another real step toward victory.

The horrors and realities of life-and-death war are one of the most

compelling and true pictures of the Christian life. God has written this

into history, into the Bible, and (through his common grace) into

Dunkirk, because nothing else quite captures the gravity and severity of our reality.

Dunkirk uncovers a war many of us need to see, because we all need to be reminded that life is war.

By Christina Miller

By Christina Miller