Article by John Piper

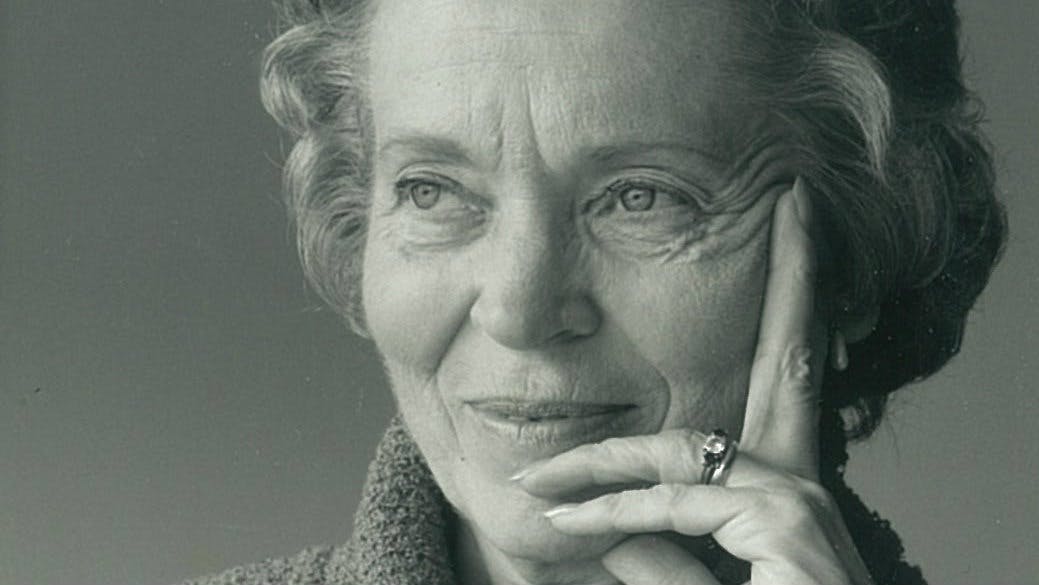

At 6:15 on the morning of June 15, 2015, Elisabeth Elliot died. It is a blunt sentence for a blunt woman. This is near the top of why I felt such an affection and admiration for her.

Blunt — not ungracious, not impetuous, not snappy or gruff. But direct, unsentimental, no-nonsense, tell-it-like-it-is, no whining allowed. Just pull your britches on and go die for Jesus — like Mary Slessor and Gladys Aylward and Amy Carmichael and Gertrude Ras Egede and Eleanor Macomber and Lottie Moon and Roslind Goforth and Malla Moe, to name a few whom she admired.

Her first husband, Jim Elliot, was one of the five missionaries speared to death by the Huaorani Indians in Ecuador in 1956. Elisabeth immortalized that moment in mission history with three books — Through Gates of Splendor, Shadow of the Almighty, and The Savage My Kinsman — and established her voice for the cause of Christian missions and Christian womanhood and Christian purity in more than twenty other books and forty years of hard-hitting conference speaking.

Her Suffering

She was not just gutsy with her words. Their daughter was ten months old when Jim was killed. Elisabeth stayed on, working at first with the Quichua, but then, astonishingly, for two more years with the very tribe that had speared her husband.

In July 1997, I wrote this in my journal:

“Just like Jesus, and Jim Elliot, she called young people to come and die.”

This morning, as I jogged and listened to a message by Elisabeth Elliot which she had given in Kansas City, I was deeply moved concerning my own inability to suffer magnanimously and without pouting. She was vintage Elliot and the message was the same as ever: Don’t get in touch with your feelings, submit radically to God, and do what is right no matter what. Put your love life on the altar and keep it there until God takes it off. Suffering is normal. Have you no scars, no wounds, with Jesus on the Calvary road?

Just like Jesus, and Jim Elliot, she called young people to come and die. Sacrifice and suffering were woven through her writing and speaking like a scarlet thread. She was not a romantic about missions. She disliked very much the sentimentalizing of discipleship.

We all know that missionaries don’t go, they “go forth,” they don’t walk, they “tread the burning sands,” they don’t die, they “lay down their lives.” But the work gets done even if it is sentimentalized! (The Gatekeeper)

The thread of suffering was not just woven through her words, but through her relationships. Not only did she lose her first husband to a violent death three years after they were married; she also lost her second husband Addison Leitch four years after her remarriage.

Now it’s time to reveal a little secret. For seventeen years, I have from time to time spoken of a certain woman on a panel with me about the topic of world missions. This woman had heard me speak on Christian Hedonism. So, on the panel she said, “I don’t think you should say, ‘Pursue joy with all your might.’ I think you should say, ‘Pursue obedience with all your might.’” To this I responded, “But that’s like saying, ‘Don’t pursue peaches with all your might; pursue fruit.’”

Well, that was Elisabeth Elliot and the panel was at Caister (the EFIC summer gathering) on the east coast of England. She was allergic to anything that smacked of mushy, mawkish, sentimentalistic emotionalism. Amen, Elisabeth! Oh, how I loved sparring with someone I could not have felt more in tune with.

Her Womanhood

And then there was her tough take on feminism and her magnificent vision of sexual complementarity. When Wayne Grudem and I looked around thirty years ago for articulate, strong, female complementarian voices to include in our book Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, she was at the top of the list. But the list was not long.

“Thirty years ago, she was already seeing with the eyes of a prophetess.”

Partly because of her voice, that list today would be so long we would not know where to stop. I love her for this influence. Her chapter in our book is called “The Essence of Femininity: A Personal Perspective.” The title is intentionally (and typically) provocative. She was already seeing with the eyes of a prophetess.

Christian higher education, trotting happily along in the train of feminist crusaders, is willing and eager to treat the subject of feminism, but gags on the word femininity. Maybe it regards the subject as trivial or unworthy of academic inquiry. Maybe the real reason is that its basic premise is feminism. Therefore it simply cannot cope with femininity. (395–96)

She spoke, on the one hand, “from the vantage point of the ‘peasants’ in the Stone-Age culture where I once lived” (395), and on the other hand from a sophisticated vision of how the universe is put together:

What I have to say is not validated by my having a graduate degree or a positon on the faculty or administration of an institution of higher learning. . . . Instead, it is what I see as the arrangement of the universe and the full harmony and tone of Scripture. This arrangement is a glorious hierarchical order of graduated splendor, beginning with the Trinity descending through seraphim, cherubim, archangels, angels, men, and all lesser creatures, a mighty universal dance, choreographed for the perfection and fulfillment of each participant. (394)When we deal with masculinity and femininity we are dealing with the “live and awful shadows of realities utterly beyond our control and largely beyond our direct knowledge,” as Lewis puts it. (397)A Christian woman’s true freedom [and, of course, she would also say a Christian man’s true freedom] lies on the other side of a very small gate — humble obedience — but that gate leads out into a largeness of life undreamed of by the liberators of the world, to a place where the God-given differentiation between the sexes is not obfuscated but celebrated, where our inequalities are seen as essential to the image of God, for it is in male and female, in male as male and female as female, not as two identical and interchangeable halves, that the image is manifested. (399)

Her Teeth

Finally, I loved her because she never got her teeth fixed. I would still love her if she had gotten a dental makeover to pull her two front teeth together. But she didn’t. Am I ending on a silly note? You judge.

She was captured by Christ. She was not her own. She was supremely mastered, not by any ordinary man, but by the King of the universe. He had told her,

Do not let your adorning be external — the braiding of hair and the putting on of gold jewelry, or the clothing you wear — but let your adorning be the hidden person of the heart with the imperishable beauty of a gentle and quiet spirit, which in God’s sight is very precious. . . . And do not fear anything that is frightening. (1 Peter 3:3–4, 6)

“She was supremely mastered, not by any ordinary man, but by the King of the universe.”

Whether it was the spears of the Ecuadorian jungle or the standards of American glamor, she would not be cowed. “Do not fear anything that is frightening.” That is the mark of a daughter of Sarah. And in our culture one of the most frightening things women face is not having the right figure, the right hair, the right clothes — or the right teeth. Elisabeth Elliot was free from that bondage.

Finally, she wrote, “We are women, and my plea is Let me be a woman, holy through and through, asking for nothing but what God wants to give me, receiving with both hands and with all my heart whatever that is” (398).

That prayer was answered spectacularly on the morning of June 15. For her, from now on all fruit is peaches. I am eager to join her.